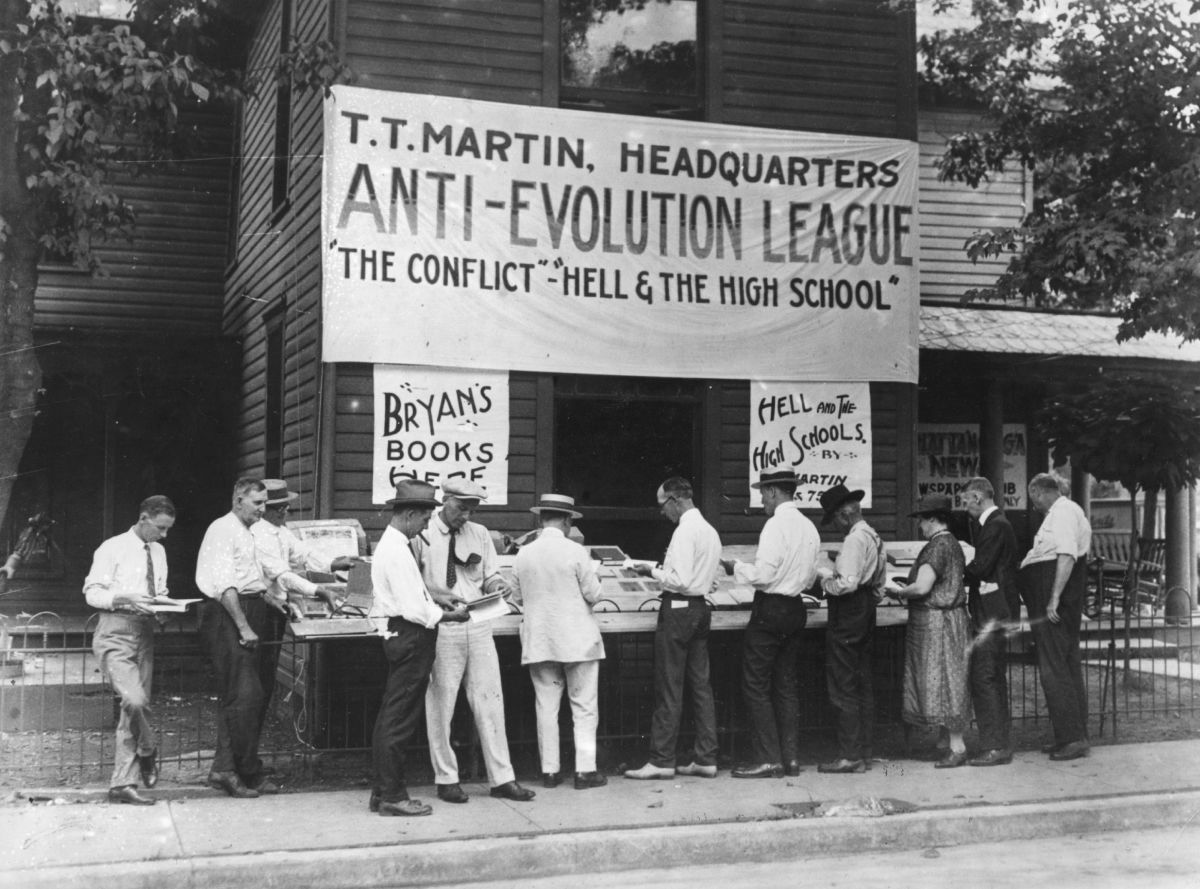

Censorship in American public schools has recently been a highly debated topic on American news channels and in the country’s social discourse. The idea of restricting access to information in this setting is nothing new, the most notable instance in the early twentieth century being the infamous Scopes Monkey Trial.

But with the concern for censorship in schools growing amid the backdrop of school board meetings derailed by diatribes about “critical race theory” and the recent passage of Florida’s Parental Rights in Education Act (the “Don’t Say Gay” bill), many teachers across the nation have been forced to confront what censorship in public schools means for their role in the education system.

To break down censorship on a local level, The Weekly Talon interviewed multiple well-known Davie County High School teachers. For the most part, the teachers interviewed had their own ideas of what censorship was and how they would respond to it. While some teachers focused on book censorship, others focused on political, societal, and historical censorship in school. But overall, no matter what type of censorship teachers were referring to, DCHS teachers disapprove of censorship in schools.

When reading this article, please keep in mind that these are individual people with their own individual opinions. They have answered because they were asked. We have also edited some of the quotes for brevity and clarity.

How do you feel about censorship?

Ms. Dunn, an English teacher says, “There are different issues at hand. There’s censorship of a government to a people. That’s super scary. That ought to be concerning; that’s what autocratic leaders do. The first thing they do is start to censor ideas and written text. But what is also very concerning is groups of people who are trying to remove books from libraries; school libraries, public libraries, and that’s a slightly different issue. Both of those are a little bit dangerous.”

“I guess it depends on what your definition of censorship is. Does censorship mean that you’re censoring content that’s not suited enough for age and maturity? Or does censorship mean ‘this doesn’t agree with my worldview; I don’t want anyone to see it?’ Because I’m not going to have a second-grader read The Things They Carried, is that censorship? I don’t think it is, I think that’s what’s grading what’s appropriate for you. However, that becomes a logical fallacy of a slippery slope argument because then who gets to decide what’s censorship and who gets to decide when it’s right for you?” Mr. Ferebee’s last question brings up a very good point in regards to the definition and application of censorship. Censorship itself is so prevalent in our schools and the country as a whole, but has no clear rules and restrictions supporting what it should and shouldn’t be based off of every individual.

Another teacher takes a more judicial approach, “I believe that if freedom of speech interferes with the Constitution that the government has a right to censor. As a citizen within this Nation, all are bound by the Constitution. With that being stated, there is a process to amend the Constitution and a right to protest any law that violates individuals rights. People have the right to question and act upon injustice in court with appeals, in law by electing congresspeople, and in society through activism.”

Mr. Wood the Holocaust and Peace Studies teacher said, “Censorship is unnecessary. People need to understand why people think, believe, or look at a certain thing or item from a certain perspective… There’s no way you can censor something if you want it to be taught. Education and teaching should be taught to give students choice. If I only teach them and censor certain information, I am no longer giving them the choice on what they pick, I’m limiting their options. In my classroom, as long as I’m teaching factual information that is rooted in fact, history, documentation, I shouldn’t be censored on it.” I think the most interesting part of Mr. Wood’s question is that he not only explores the effect of censorship for teachers but for the students as well.

Do you think the first amendment applies to schools? Do schools have the right to free speech?

“There are several court cases that would support that. Students have those rights. There are some limits to those rights according to court precedents, and people need to be reasonable and appropriate. But, yes, schools should have free exchange of ideas.” said Mrs. Dunn.

Mr. Ferebee says, “The first amendment is widely misunderstood. People think getting banned from Twitter is a violation of their first amendment rights, but Twitter is not the government; the government cannot illegally restrict you from saying something that is a constitutional right, meaning they cannot hold it against you for what you say. The only time — and then people argue “is this censorship?” — is that you can’t say something when it’s directly endangering someone else. But to me, I don’t think that’s censorship. I don’t think that falls under the first amendment because if we’re in the school and I yell ‘I have a bomb,’ I’m now endangering everyone in the school. So not saying that is not censorship — it’s public safety. But again it goes back to who gets to decide that line? “

Mr. Wood gave an incredibly direct answer. “Yes. As long as people are learning, why should we take away from that? Your job (as a student) is to be educated. My job is to not force something down your throat but give you perspectives and information to shape and mold what you believe, and you take that to the next level of your life, pass it on to your children, or you learn at a higher level of education. But you learn and continue that learning development.” He then relates the idea of censorship and the enforcement of the ideas presented in the first amendment to Nazi Germany and Joseph Stalin. “Censoring information turns into, for example, Nazi Germany. Information gets censored at the education level for schools, politics, and then you’ve only got people seeing and believing one perspective, and we know how that worked for Nazi Germany. Same thing with the USSR and Joseph Stalin in the 1930s. With more open-mindedness and without censoring information, you give people the choice of freedom of what they want to learn. Choosing what to learn or what not to.”

What about censorship in schools?

Context: At the time of these interviews, 35 states had attempted to pass a total of 137 bills that would limit what teachers could teach.

Ms. Dunn said, “Parents can certainly require that their child does or does not read a title. That is parents’ rights for their own child. But, when it comes to overall titles, my thought process is that young people are in school to consider a range of ideas, a range of topics, subjects, and — in some cases — to have some deep discussion, sort of exploring their thoughts. And so imposing limits on ideas, or removing titles, without very careful consideration, I think is not the way to go. Very limiting for people. Dangerous in a free society, really.”

Another English teacher, Ms. Edminson said, “I don’t like the idea of anyone policing what we can and cannot read. I understand the theories behind censorship, and I’m hopeful that it’s well placed and that it’s well-intentioned. But statistics show that students who read anything — anything they read — become better equipped across the board — in every subject area, in writing and comprehension, if they read. So, I would hate to have something snatched from the hands of someone because someone else said ‘that’s not a good book to read’.”

Mr. Robinson, someone who has contradictory opinions, discussing parental rights and the fact that the history he was taught as a student was heavily censored, says, “I have two opposing views. I think that parents and the community absolutely have the right to influence what is taught in public schools. I also think that perhaps the versions of history that I was taught have been filtered. I was taught that General Robert E. Lee was a noble gentleman and a noble soldier. In retrospect, that was probably a propaganda ploy. So, I think that the versions of history we’ve been taught have been filtered, but I also get very nervous when educators take it upon themselves to enlighten people to the new progressive attitude. So, on one hand, we have some profound misconceptions, and I was probably educated with the version of history that was highly ‘sanitized’. But on the other hand, I don’t think that the educators have the right to cram very progressive views down the parents’ and the childrens’ throats. Our job as educators is to teach children to think. Our presentations should be balanced; not heavily weighted to one side and a straw man on the other. Students should be taught that critical thinking involves weighing both sides of an issue fairly, thoroughly, and respectfully.”

Now that teachers are having to reevaluate their curriculum, would their job become harder?

Ms. Edminson explained, “I do think so because then all of a sudden everyone could judge the reading material that any teacher, myself included, puts out there. And all of a sudden, I would be looking over my shoulder instead of giving students what I believe would be a good educational read. And that would be very difficult. I don’t know if I could be a literature teacher with censorship in place.”

Mr. Robinson offered an interesting view on possible censorship in math, which at the beginning I didn’t believe existed, “If a bill passed could it affect what I teach? Possibly. In math, if they told me that ‘you can only teach math, you cannot deviate from the curriculum whatsoever’ and I’ve had people tell me that, that ‘you can’t teach physics, you can’t do this, you can’t do that, you have to strictly follow the curriculum.’ If there was a bill to that effect, yes it would affect me.” Mr. Robinson has been working to make his curriculum applicable to the real world, using questions that fit into daily life and involving students in more hands-on activities.

Mr Wood, as an American History and Holocaust and Peace Studies teacher, deals with a lot of seemingly heavy and controversial topics. “Absolutely it would. When you think about censorship from a political standpoint, if we were only allowed to teach certain things in history, that would limit ideas that are taught in the classrooms, such as about slavery and the hardships faced by immigrants. That would also limit talking about the negative things America has done around the world, which has to be taught. Even though America is a great nation, it’s also equally important to know that we have done our terrible share of things and we have to learn from them; we have to know it. Because around the world, that’s what’s taught about America, not necessarily the great things, but about American slavery, American war crimes, proxy wars, those things need to be taught.” Mr. Wood then goes on to explain that his curriculum would change drastically, and that he “would be told how to teach a certain way and what to teach, and that’s not how I teach. I would seek employment in another county because I teach what I believe my students should know to make them better humans and better Americans. Not to make them part of some agenda.”

Are there things that should be censored?

As he ties back into age-appropriateness, adding in the lack of personal life experience Mr. Ferebee says, “Are there some contents I think are probably not appropriate for people of this age? Sure. I think there are things that even the brightest and most inquisitive of you are just not ready to handle because you don’t have the life experience yet. And it’s not because you’re not interested, it’s not because you’re not academically smart enough, it’s not because you don’t want to have those discussions, but you haven’t experienced enough of life to have the background knowledge to discuss it from anything than what you’ve heard other people say or what ideas you come up with in your mind. So, I think censorship is a tough word there, but I think there are definitely topics that are beyond the scope of high schoolers.”

Mr. Wood says, “Age level appropriateness. 11/12-year-olds, all the way to seniors in high school — nothing should be censored. Let’s be honest about the realities in America; let’s talk about real American history. Teach these things (true sex education, LGBTQ rights) at a young age, but build on it. Tier it. Start with small doses and then by the time that you reach your senior year of high school, you should be fully educated and know what these things mean because those are things you are going to encounter in the real world that you might not see in Davie County. Our job as teachers is not to prepare for life in Davie County, but for wherever you go: military, college, for the workforce. But you have to be knowledgeable in these areas.”

A proposed law in South Carolina prohibits the teaching of any subjects or topics that may cause students to feel “guilt, anguish, or discomfort.” What’s your take on this?

Ms. Dunn, like the other teachers, says that discomfort can be good. “So, I am a big proponent of the idea that discomfort is sometimes the thing that makes you learn the most. Removing discomfort from the lives of your children is asking, in my mind, for mental health issues in their adulthood. I just don’t understand that concept, the idea that what another generation of people did would cause me to feel guilty. I mean, I reject that. I think in schools, you help young people understand some really complex issues and make up their minds about certain things. You don’t tell them what to think, but give them tools that would cause them to be able to think and practice thinking. So, yeah I think that’s also super dangerous, to say ‘this topic is off-limits,’ we probably don’t talk about uncomfortable issues and pretend that they’re not there. In some cases, I don’t see that as the way to go.”

Ms. Edminson says, “I think there are some things that as a people, as a United States people, that we should feel ashamed about and that it should make us upset. And to gloss over that, I don’t think that would solve anything. We all hear about racism and how endemic it is. Well, that’s because we don’t talk about it, because we are so afraid of hurting people’s feelings or the backlash of what we might have said or done and the fallout from that, that we just kind of breeze over it. And if we, as a people, keep deciding that some uncomfortable topics should just be avoided, then we’re not doing our jobs as educators. Some of the things that are so disgusting about our history, we need to put it on a line and air it out. We need to move past it, and we can’t move past it if we keep pretending it didn’t happen, or that the wrong versions are misleading what really happened.”

One teacher brings up the ambiguity and wording of this bill. “I feel curious and a bit skeptical. How do they define these terms? I feel guilty when I eat chocolate chip cookies. Does that mean they should be banned in schools? People feel guilty when they don’t study enough for tests. Should we not talk through tests and help students see the value in test-taking strategies and skills? Before you are quick to say ‘this is different,’ hear me out. All of those terms (guilt, anguish, discomfort) are extremely subjective and depend on the life experience of individuals in order to know where the “line” is. The things they (legislators) may define as those terms will only make a certain percentage of the population uncomfortable or comfortable. So where is that line? I would need detail to ensure that they have an actionable law (law guidelines state that laws should be public, fair, stable, and understandable). Guilt has also been proven by psychologists to cause deeper discussion and lead to positive change. It is shame that causes long-term negative impacts. Maybe they should be using the term shame? Or at least discussing with professionals in related fields. The world is tough and discomfort is unavoidable. We must learn and grow together. Will these laws build capacity for that? Do they value and trust educators and professionals? If society shows that we can’t trust educators, how much harder does that make the work of teachers?”

Mr. Wood related this idea of uncomfort and anguish to his curriculum. “When you think about a nation’s history, or when you think about the US, in my classroom, we talk about — and we love to talk about — what other nations have done. We talk about Germany and the Holocaust. We talk about communism and what has happened under communism. But when it comes to talking about what the American government has done, that’s one of the things that make people uncomfortable. It should be. History isn’t comfortable. History is filled with awful truth. It’s filled with death, it’s filled with slavery, it’s filled with racism. But it must be taught. If you are uncomfortable, that means you are learning. You are learning when you are uncomfortable. If you only teach things that show things in a good light or a certain perspective then people are going to have a false notion, a false sense of who we really are, and not what this country has truly been about.”

If a bill were to be passed in North Carolina that censored teaching, what would you do?

“I’m a little bit unique in that I can walk out the door at any moment.” says Ms. Dunn. “I’m well past retirement age, and that gives me freedom that if the North Carolina legislature did something, I’ll just be done.”

Mr. Ferebee, seeing as how a few teachers said they would leave, makes an interesting prediction. “I think that what you’re going to see happen — and this is purely speculative; I have no data whatsoever, so this is my anecdotal answer — I think that having these things happen (whether they’re intentional or not, or if they are trying to gain a certain thing or not), then you’re going to have the people leave those places who can leave those places: people who don’t want to deal with it. And what that leaves behind is a bunch of people who don’t want to deal with whatever it is. And that never leads to a good place. Regardless if that’s a left-leaning thing or a right-leaning thing, or not political at all, if you only have a bubble of whatever it is you believe, that is never a good thing.”

Mr. Wood, as Mr. Ferebee speculated, “I would turn in a resignation letter, depending on what it would be and I would leave public school in North Carolina. As long as I’m molding my students into better teenagers and into better humans and better citizens of America, why should I be limited on what I teach? Censoring information is how you create misinformation. If you start censoring what we believe and you turn us all into believing one thing, you’ve taken away our first amendment right of freedoms.”

A fourth teacher says, “If it is the law then it is the law. I am not sure the purpose though if parents have a different ideology on school- one of the many awesome parts of our country allows for school choice. There are charter and private schools that can control the output beyond the state standards (private schools do not have to abide by standards at all).”

Florida’s Parental Rights in Education Act, or the “Don’t Say Gay” Bill, has sparked a national word war. What do you think about this type of censorship?

Mr. Wood says “I absolutely disagree with that too. Homosexuality has been a part of our world since we’ve known it, as early as Greek life and the Romans. People are going to be gay and people should learn about what it means to be gay. At the end of the day, regardless if you’re gay, straight, trans, or even if you’re not specific to any gender, at the end of the day you’re still a human being. And human beings all matter, regardless of their beliefs, regardless of who they are with their sexuality.”

One teacher looks at it through the scope of court rulings and precedents. “I am curious as to how levels of censorship have been precedent in our courts. From my knowledge vantage point, this level of censorship has failed within years of attempted initiation. Based on those Supreme Court rulings of Constitutional censorship, I am not sure this is constitutional.”

Ms. Edminson replied in detail saying, “Fear of knowledge must be part of the human condition; we see it pop up all the time in our modern culture. People in positions of authority debate whether or not those of us in the ‘general public’ can be trusted with sensitive information. We have warning labels on certain shows, videos, and music; firewalls around various sites, for the protection of vulnerable populations. I choose to believe these are not intentionally restrictive but meant as a safeguard. I wonder, however, who decides and regulates what is forbidden? In a free society, which group posts the guard at the door of access?” This question has been one shared by many teachers, but Ms. Edminson wasn’t done. She goes on to say “I guess I have viewed censorship primarily as a limit to one’s reading or writing choices. That’s logical due to my subject area! Recent events in Florida and Texas that have engendered discussions and debates far and wide have broadened my thinking of censorship. I still believe that restricting any topic limits knowledge, and I am against that. When those restrictions move into public classrooms in the realm of compulsory education, I can understand the motivation to fear and/or censor what may be said, shared, exchanged at school, as well as what may be read or written in class settings.”

Do you think the introduction of ideas such as sexuality, gender orientation, etc. should be left to parents?

“In the school system, from a certain age, it should be taught,” says Mr. Wood. “Parents, regardless of their beliefs, this is something we are encountering for this generation. And regardless if parents like it or not, this is the world we live in. The world is constantly changing. We can’t just confirm or keep things the way they are. Change is going to happen. That doesn’t mean that you’re going to force what it means to be trans down someone’s throat, but you teach the meaning behind it — what it means to be straight, what it means to be gay, what it means to be bi, what it means to be genderfluid, pansexual. Teach these things to children, build upon it, so that way teenagers, such as yourselves, can understand people around you and the struggles they go through.”

Another teacher says, “The job of the school system is to help prepare students to be active, productive, and successful members of our society. All of the mentioned topics play a role in our society and therefore the school should help students have a broader understanding of people similar and different than them.”

Mr. Ferebee states: “I do not think that the education of these topics should only be left to parents, no. It is important to keep in mind the fairness of education and that your personal beliefs as an educator are your personal beliefs and should not become doctrine. These are topics that many people do not want to discuss for various reasons, but that does not mean that we can ignore them. People need to feel represented and see representation as that is crucial to personal development. The more we sequester subsections of our population because we don’t want to broach such issues, the more we alienate people. These topics should be discussed in education, but ultimately an educator’s job is to inform students about topics, not to demand similar ideals.

Other thoughts?

Mrs. Dunn kept her other thoughts short and sweet, but nonetheless powerful, “A free society has the freedom to read.”

Ms. Edminson: “At Davie, I teach all levels of students, and I can’t think of any students that would be unwilling or unable to grasp hard decisions, hard topics, hard things. I don’t think anyone would say ‘stop you can’t tell me about that because it’s going to upset me,’ or at least I like to think that way. And teachers, educators, are supposed to be shining that light, encouraging people to be free thinkers, encouraging people to be critical thinkers, and if someone doesn’t like something that I’ve said, know what to do! Google it. Research it. See if I’m right, or if I’m wrong, or if I’m biased and call me out on it, and call each other out on it. But let’s get to the bottom of it. And if it’s true, then let’s bring it into the light and talk about it. Or else we’re going to keep having lots of societal problems that we don’t really need to have based on misunderstanding or head-in-the-sand thinking. ”

Mr. Robinson expresses his conflicting views again, “I’m really conflicted because on one hand, I don’t think the parents of Davie County should have their children subjected to extreme agenda-driven views. I don’t believe that educators with an agenda should have free reign to push their agendas on the parents and children of Davie County. But on the other hand, I do believe that old people like me may not be aware of many of the horrible injustices that have been committed in our nation. These need to be brought into daylight and discussed or we will never heal. We will not survive as a nation if we do not heal. Nevertheless, I believe that our Country is the best ballgame on the planet. Right now, we are going through some growing pains. If we work hard to listen to each other, we will survive.”

Mr. Wood finishes with a message for his future students and his fellow educators, “My job as a teacher — I do not just cater to students who are Christian or who are straight. I cater to every single student that I interact with. Those are my pupils. I have to learn about them, I have to care about them, and I do care about all my students. My job is to make sure that in my classroom they feel safe and they feel understood. And that means that anyone who walks through my classroom, regardless of how different they may feel, at the end of the day we are all the same, but my job is to teach multiple perspectives. I have to cater to everyone because if I’m not doing that, then I’m not doing my job and I’m failing students that feel that they are indeed different, and that’s not fair to them, nor is it fair to the people of this school.”

Our teachers do not seem to like censorship. It can be harmful both to themselves and to their students. The rules of censorship are open to far too much interpretation. Schools can’t draw that line, deciding what should and should not be censored. There are so many questions that need to be answered: What is censorship? What does it look like? Is censorship becoming more harmful than it is helpful? Is this going too far? What does this mean for the future of our schools? We don’t think anybody really knows, and that’s part of the problem. Without a clear definition and rules, the idea of censorship can be skewed to limit any topics or ideas that can be taught because some people may not agree with them.